Siyabonga Hadebe | Thursday, 6. June 2024

Big Capital’s preferred coalition partnership involving the ANC and the DA must be read using its historical and current role in South Africa. Corporate South Africa is perhaps the most powerful ‘entity’ in post-apartheid South Africa. Some people argue that it has more power than it had during apartheid. Wits academic and sociologist Roger Southall traces this rather bizarre state of affairs from the ANC’s decision to present itself “as a partner with which large-scale capital could play.”

First and foremost, to understand how Big Capital has shaped the politics of South Africa to date, one needs to look no further than Harry Oppenheimer and his larger-than-life company, Anglo-American. This company occupied centre stage throughout the apartheid era, and former apartheid prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd is said to have remarked that Oppenheimer could collapse the South African state at any time.

Indeed, as the apartheid government tightened its grip on the rebellion by the African majority at the beginning of the 1960s, Anglo American’s prominence grew even further. The killing of scores of Africans in Sharpeville on 21 March 1960 resulted in a significant capital flight out of South Africa. Anglo-American Corporation’s enormous capital resources helped stabilise the situation and prevent economic collapse.

The New York Times wrote in 1983 that Oppenheimer’s “grip on the country’s resources had never been translated into effective political power.” Thus, after the Sharpeville massacre, he had the opportunity to truly influence the course of events within the South African state.

Oppenheimer’s advantage was that he “personified the one power centre the Government party had never quite managed to dominate.” As a result, tensions always existed between these two centres of power. The Nationalist Party always lamented the power of ‘British-Jewish capitalism’ in the same way present-day black nationalists complain about ‘White Monopoly Capital’. History, it seems, has a way of repeating itself.

With all the tension that existed at the time, “The Nationalists gradually learned to depend on Harry Oppenheimer to save them from the economic consequences of their own policies.” As noted above, the Sharpeville massacre created an untenable situation for the Nats — a catastrophic flight of Western capital. This is when Oppenheimer’s money came in handy.

His billions assisted South Africa to slowly recover and set the country on the path to becoming a sophisticated industrial state. Bill Freund cites the example of Oppenheimer’s gift to Afrikaners through the creation of Gencor. The company marked the entry of Afrikaners into mining. South Africa went on to depend on Anglo-American, which controlled almost every aspect of its economy.

The void left by the companies that departed South Africa gave Oppenheimer the power to literally control much of mining and the economy. He was the king of diamonds, platinum, vanadium and uranium. Today, these minerals are key to the green climate agenda. According to Duncan Innes, his companies also produced coal, steel, nonferrous metals, pulp and paper, automobiles, fruit, wine and more. His empire extended to banking, insurance and real estate.

All in all, the Oppenheimer dynasty accounted for roughly half the value of South Africa’s exports and half the value of the shares traded on the JSE. And that was only in South Africa. His wings stretched to Zimbabwe, Namibia, Botswana, Tanzania, and—very discreetly—Angola and the USSR. Oppenheimer and Anglo-American even managed to beat the tight exchange controls to own businesses in the USA. The flexible exchange controls were only introduced under the new black government in the late 1990s.

In 1983, the British weekly, The Economist, estimated Oppenheimer’s wealth at a whopping USD 15 billion. Much of this money needed to leave South Africa and something had to be done. It is suggested, “From late 1984 onwards, a series of meetings between the exiled ANC and groupings from within South Africa [particularly the members of Corporate South Africa] began to take place, a process that was unprecedented, especially since the ANC had been banned since 1960 and was prohibited in any form inside the country.”

As far back as 1985, authors David Pallister, Sarah Stewart and Ian Lepper observed, “The most striking aspect of the South African economy is the degree to which it is dominated by just a few large companies…” This can be attributed to the dominance of Anglo-American and the historical role the state played in the economy in its efforts to empower the then-poorer Afrikaners in relation to their English-speaking counterparts.

The questions that remain unanswered and continue to trouble many people are: Why did Capital negotiate with the ANC in exile and not the apartheid government? Why would the very same companies that directly benefitted from racist laws turn against the hand that fed them? Answers to these questions would hopefully provide compelling reasons that motivated Corporate South Africa to hurry in approaching a banned liberation movement and to understand exactly what the catch (deal) was crafted for the exiled ANC leaders.

Without the Oppenheimers and their unparalleled foresight, one doubts whether these meetings would have occurred. Oppenheimer is/ was the god that everyone in South Africa worships/ worshipped. The money buried within South African borders and economic sanctions, to a lesser extent, pushed white businesses to talk to the ANC. It was more the pariah status that was a huge problem rather than concerns for human rights and economic sanctions, which are often exaggerated by some.

Nonetheless, Capital needed to be seen reaching out to black South Africans to make an impression on the international community. This was merely a formalisation, considering that the West (Britain) never truly turned its back on South Africa. Moreover, a company like Anglo-American was already a multinational corporation with interests all over the world. Therefore, it was important to prepare the ANC for what to expect when it came to power through a negotiated settlement.

With a floundering organisation in exile, the approach by white businessmen was a godsend for ANC leaders. It can be argued that they were negotiating from a position of weakness, as they had no serious bargaining power. They were also racing against time as the Soviet Union was beginning to unravel. Additionally, Southall points out, “Just as the ANC was unable to overthrow the political order, so it was unable to overturn the economic order.” There was no other route that the ANC could follow besides dancing to Corporate South Africa’s music.

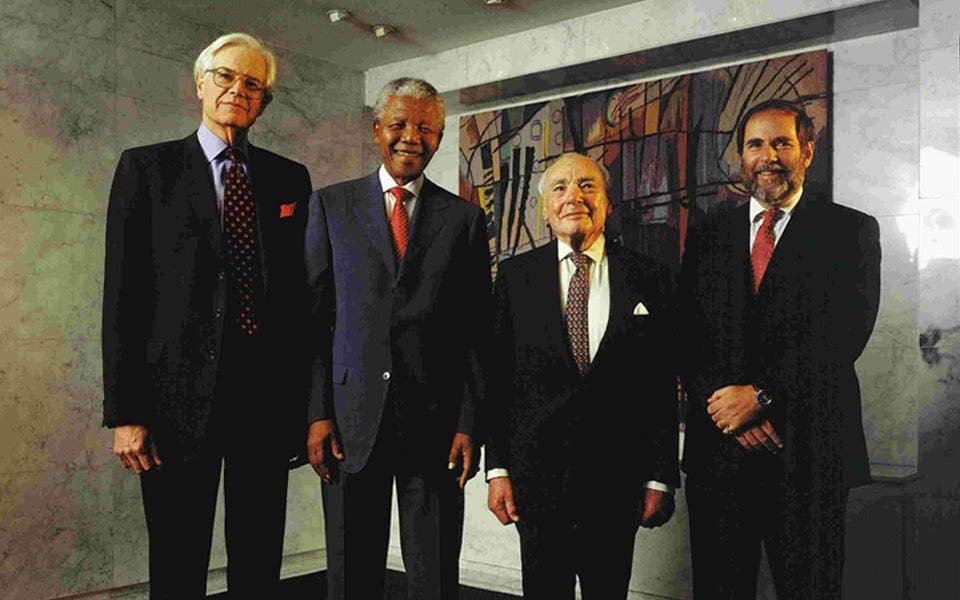

However, what seems to be a point of interest is the nature of the economic benefits that the ANC likely expected from white businesses in exchange for some political agreement. Besides the ‘donations’ given to its leaders, such as houses, cars and cash, black economic empowerment (BEE) became the mainstay of uplifting former cadres and others by large businesses after the fall of apartheid. Also, figures like Nelson Mandela “forged strong relationships with both Harry Oppenheimer, Chairman of Anglo-American and Clive Menell, vice chairman of the rival Anglo-Vaal mining group.”

Nonetheless, it is important to point out that the idea of BEE was not conceived solely after the end of apartheid but much earlier. Opposition figures who were liberals, such as United Party leader Sir de Villiers Graaff, believed that “the permanently detribalised Bantu should get the right of representation in Parliament as a separate group” as well as rights to home ownership in their own areas and freedom of movement. The purpose was to “develop a responsible property-owning Bantu middle class in whose interest it would be to accept the responsibility of ensuring not only peace but also Western standards.”

Oppenheimer himself, also a sponsor of the United Party, once told Anglo-American stockholders that “South Africa would not follow the pattern of other African countries by handing over power to blacks.” It was through the Urban Foundation, his personal project, however, that Oppenheimer outlined his vision of building up “a black middle class as a bulwark against revolutionary elements, and to provide a stable community with solid materialistic values.” In fact, Oppenheimer had previously employed a similar strategy with Afrikaners in the 1960s.

The BEE policy was a gift given to the ANC-led government by Anglo-American, which was responsible for distributing patronage to cadres as a thank-you for leniency towards Capital. Sociologist Donald Mitchell Lindsay, in his PhD thesis titled BEE Informed: A Diagnosis of Black Economic Empowerment and its Role in the Political Economy of South Africa, reveals that one ANC cadre, who had just been released from prison, had his name suggested that he “be given the De Beers Venetia Diamond Mine in Limpopo in exchange for his political support,” as per information provided by Michael Spicer, an ex-Anglo executive.

Lindsay claims that Oppenheimer did not agree to this proposal. Instead, Oppenheimer “suggested an alternative package of assets for this individual who, today, is one of the richest and most politically influential men in South Africa, largely on the back of unproductive BEE-type investments. He is also a member of the NEC of the ANC.” This illustrates how BEE was operationalised and how it primarily benefited the politically strong within the ANC. The ANC’s recent election campaign proved that these loyalties never die quickly.

It is important to note that BEE was never an economy-wide policy; it initially started in mining and later replicated in other sectors. That explains why mining BEE codes were different from the rest. The minerals and trade departments have not harmonised the two sets of BEE codes. Mining has a 26% requirement, which Mosebenzi Zwane wanted to increase to 30%.

The Mining Chamber opposed changes, arguing ‘once empowered, always empowered’. They contended that influential individuals had already received patronage. The perception that the ANC is a “machinery for accumulation,” using Roger Southall’s phrasing, is not far from the truth considering how BEE turned cadres into instant billionaires on a whim.

In summation, the creation of the BEE threshold in mining essentially shielded Oppenheimer’s assets from potential nationalisation. Additionally, it diverted wealth that could have been part of the national patrimony to individuals under the guise of empowerment. On his part, the King of Diamonds could do as he pleased because he owned minerals in the region and had the power to determine political outcomes. Everyone across the ‘tension line’ bowed to him, from PW Botha in apartheid South Africa to Zambia’s Kenneth Kaunda.

What is not always said is that Oppenheimer did not assist the ‘new’ South Africa or Botswana as he did with Israel. He “personally directed that Israel receive the necessary diamond raw products from De Beers to establish itself as one of the world’s diamond polishing and exporting countries.” While South Africa and Botswana served as extractive colonies where he amassed his wealth, Israel was strategically positioned in the tertiary side of the diamond processing value chain despite lacking a single diamond mine.

South Africa has a handful of billionaires who unfairly attained their wealth from Oppenheimer, who undermined the democratisation project. Oppenheimer used BEE to protect his massive financial interests and his financial muscle to manipulate economic policy to take his billions out of South Africa. Anglo-American is one of the companies that benefited from flexible exchange controls; they used this policy change to relocate to overseas markets. Now, Anglo-American plans to exit South Africa altogether in one of the biggest shake-ups in the company’s 107-year history.

Capital continues to shape the South African political landscape to this moment. It used its strength to determine the outcome of the ANC conference in 2017 and now aims to influence the outcome of the 29 May election to create an ANC-DA coalition. This reality means that the South African state exists in the shadow of powerful companies – the reasonable conclusion is that Big Capital will continue to exert pressure until it is viewed positively across the political spectrum.

Big Capital has no short-term intentions to abandon the country but keeps pressure on South Africans using power levers like high unemployment, social stagnation, low growth and the ‘investment strike’ to flex its muscle more than anything else. This perpetuates the deferral of freedom for the black majority, illustrating the influence of Big Capital and its rentier capital offspring (BEE and other ‘corporate gifts’) in maintaining economic inequality and political control.

¡Si ya banga le economy!